I moved to Edinburgh in 1986 because of Peter Higgs, and I'm still here. He surely had a bigger influence on the lives of many others, but he had a pretty big impact on mine.

In 1986, I knew I wanted to do a Ph.D., but I wasn't entirely sure what it should be in. Theoretical Physics? Maths? AI? I applied both to AI and Physics in Edinburgh, and interviewed for both, But from the moment I received the invitation for interview in Theoretical Physics at Edinburgh, I knew I'd go there if I possibly could.

Because Edinburgh Theoretical Physics did something very smart. They got Peter Higgs to sign the letter inviting me (and, I'm quite sure, everyone else they invited) to interview.

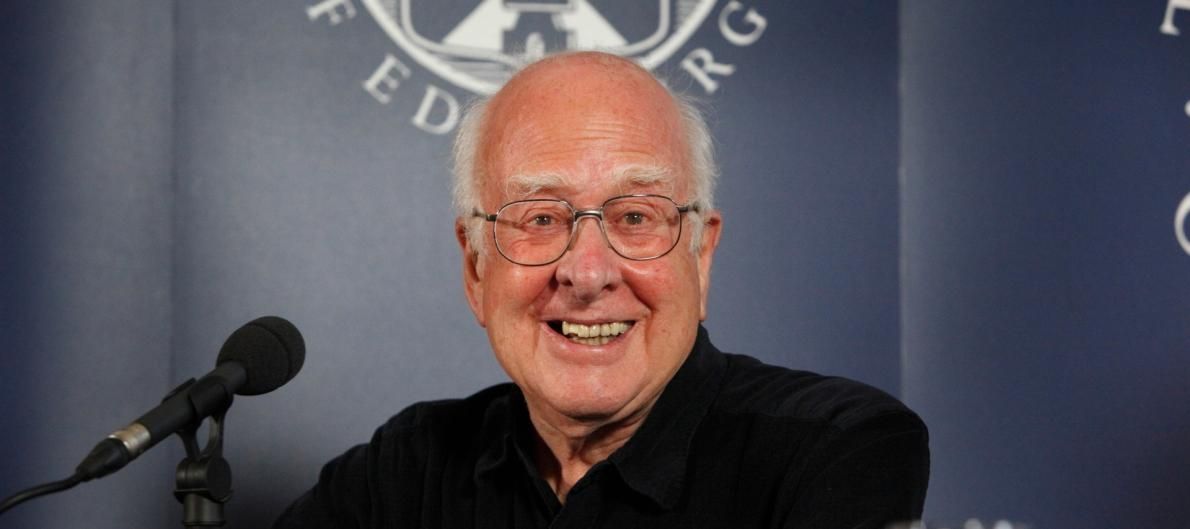

These days, everyone knows who Peter Higgs is. He got a Nobel Prize. He has a particle named after him ('the particle usually referred to as the Higgs Boson', he normally said). He's famous.

But in 1986, his fame was more limited. I knew him, because I was obsessed with particles and the nature of the universe and he was one of a tiny handful of people who had a particle named after him (albeit one that hadn't, technically, been found at that point). Who else had particles named after them? Not many people; maybe no one else. There were fermions, to be sure, named after the brilliant Italian physicist, Enrico Fermi. And there were bosons, named after Satyendra Nath Bose; but both of those are classes of particles (fermions having so-called "half-integer spin"—1/2, 3/2 etc.—while bosons have integer spin values–0, 1, 2 etc.)

Protons, neutrons, electrons, positrons, neutrinos, photons, quarks, gravitons, pions, kaons, mesons, alpha particles, beta particles, gravitons: none of them were named after people. But the Higgs Boson was.

I took the train to Edinburgh, from London, for my Ph.D. interviews (physics and AI). This was about a week after my first interview for a Particle Phyics Ph.D. in Southampton. That one had not gone well. They asked me to solve the quantum harmonic oscillator on the whiteboard. I failed to do so.

Edinburgh's Theoretical Physics Group had a fairly new head, the Tait Professor of Theoretical Physics, one David Wallace—a man with a big reputation. I'd spoken to him on the phone (for what reason, I can't imagine) before going up, and in those pre-web days, I had a very clear (but ill-informed, as it turned out) picture of David in my mind's eye. He was about 6'8" tall, with flaming red hair, a long beard, a green kilt, and was never far from a bottle of single malt whisky. When I met him, it transpired that he was fairly short, bald, grey and wore a grey suit, though it is true that we shared an enjoyment of single malts, especally Talisker; and he really did have a fearsome, and well-deserved, reputation.

I was ushered into Professor David Wallace's office and greeted by an interiew panel consisting of David (Wallace), Peter (Higgs), Ken Bowler, Richard Kenway and Stuart Pawley. "Yours is the seat by the whiteboard", they said. After a few pleasantries, they asked me to solve the quantum harmonic oscillator on the board. This was lucky, because for once in my life I'd actually learned from my experience in Southampton and read up on how to solve the bloody quantum harmonic oscillator. It's true that I was a bit put off by Ken Bowler, who groaned a lot though the first three-quarters of my exposition, apparently convinced I was going to forget the commutator; but he perked up a lot when I put it in. And I got the place. And in fact, Ken and Richard became my supervisors until they (quite reasonably) sacked me in year three upon learning I'd strayed from the true path of calculating the proton's mass; but David took me under his wing, and it all worked out in the end. I think the only two words Peter uttered during the whole interview were "Hello" and "Goodbye"; but that was enough. After all, he was Peter Higgs.

During my first year, Peter taught me and my fellow first-years (five of us, I think) all the quantum field theory I have since forgotten. I think he was a rather good teacher. I certainly enjoyed his lectures. And I seemed to able to solve the problems he set, despite my lack of methods courses at Sussex, where I did my B.Sc. It's true that neither he nor David Wallace ever convinced me that renormalization group theory had any rigorous basis at all—it largely seemed to me to me to consist of cancelling out infinities on the basis that they might be same size—but I understand the mathematicians have put it all on a rigorous footing now, and Everything's Fine;™ so perhaps I needn't have worried.

Outside the department, I saw Peter several times at the Filmhouse on Lothian Road, Edinburgh's premier arthouse cinema at the time (and sadly missed to this day, since its closure). I spent an enormous amount of my Ph.D. there, just as I'd spent a huge amount of my time at Sussex at the Duke of Yorks cinema at London Road. The first time I saw Peter there, with his son Jonny, it was to see Alexander Nevsky. Peter was clearly a bit embarrassed and said something like "Oh hello. I won't tell on you if you don't tell on me," something that took me a moment to comprehend. During my whole time at Sussex and Edinburgh, it had never occurred to me that there was anything wrong, bad or disreputable about spending afternoons watching double and triple bills of foreign films, but I suspect he thought I should have been studying quantum field theory, and perhaps that he should have been—I don't know, unifying quantum theory and gravity, I suppose.

Many years later, Peter appeared on Jim Al-Khalili's Life Scientific program/podcast. Predictably, Jim asked Peter to give a simple explanation of the Higgs Mechanism (the process whereby the Higgs Field, via the Higgs Boson, causes particles to exhibit mass). Peter declined to do so, saying that it was too complicated for simple explanations. I usually say that people with a really profound understanding of something can almost always convey something of the essential meaning of that thing to almost anyone willing to listen, so I should probably think less of Peter for that answer. And it's certainly the case that I cannot imagine either Einstein or Feynman declining to answer in that way. But, in Peter's case, and his mechanism, it seems perfect. And in truth, all the pop explanations I've ever heard of the Higgs Mechanism have been worth very little. Maybe it is just too hard for simple explanations.

So it was Peter who brought me to Edinburgh, and 38 years later, I'm still here. I think he led a good and rich life, and he lived to 94, mostly in pretty good health, so his death is no tragedy. But it still saddens me, of course. It was rare priviliege to know him a little, and to learn from him. I think he was a great man, and a very modest one. We shall be poorer without him.