Before I bought Helen Czerski's Blue Machine, I was struck by they fact that several people described the book, as 'one of the best books I've ever read'. I would not have been surprised if people had called it one of the best books on the ocean they've ever read, or one of the best science or physics or environmental books they've ever read, or even as one of the best non-fiction books they've ever read. But people consistently said 'one of the best books' without qualification.

I now know why. Blue Machine is one the best books I have ever read. Some of the reason people don't qualify the statement is probably because it's quite hard to classify. It is one the best physics books I've ever read,1 and it is also one of the best environmental books I've ever read, and it's also one of the most charming and beautiful and wide-ranging books I've ever read. Helen Czerski is a physicist who studies the ocean, but the book goes far beyond physics, full of stories and digressions on all manner of subjects mentioned as part of her survey of the ocean.

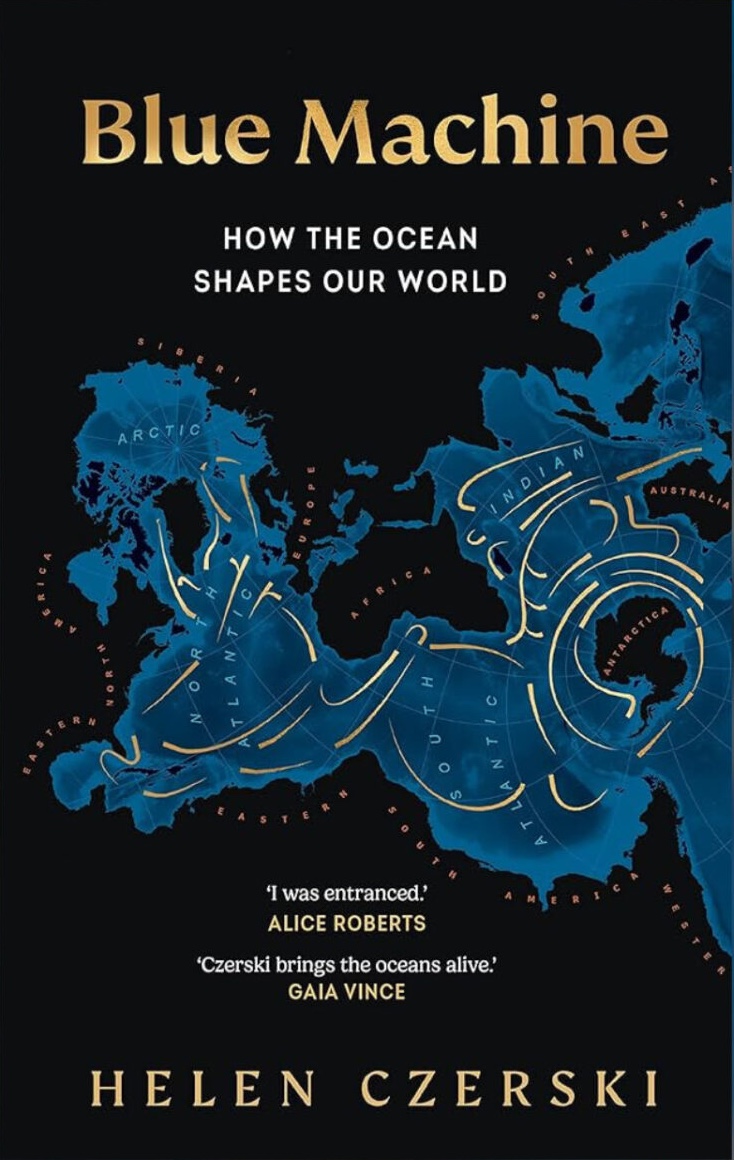

I bought the hardback edition, even though the paperback was out, almost entirely because the cover of the hardback is so fantastic (which the cover of the paperback is not). Not only is the cover beautiful, it also strongly reinforces several of the key messages of the book. It shows a map of Earth with the oceans as foreground, in blue, and the land as background in black. Where many familar projections of the Earth split the ocean in various places to allow the land masses to be shown more clearly, the projection chosen splits the land to allow the oceans to be seen unmolested. The oceans are overlaid with golden lines showing their major currents. Czerski wants us to think of the oceans not merely as absence, but as a presence; as that which covers 70% of the Earth's surface; as the home to most of the Earth's species and biomass; as the machine that provides endless services to the planet and all the life on it, but which is largely ignored, underappreciated, misunderstood, and---increasingly---altered and degraded by careless human activity.

The book is divided into three parts, two large one small. Part I (What is the Blue Machine?) is an explanation of what the ocean is and how it “works”. It is the physics-and-engineering part, expanding on the idea of the ocean as a machine more explicitly and literally than I had expected, describing the structural complexity of the oceans, the nature of the currents and gyres, the energy flows, and the way the oceans are layered and variegated in temperature, salinity, pressure and more. There is much science in here, but the exposition is more Attenburgh than textbook. Czerski is passionate, playful, interested in everything, finding stories and curios everywhere, delighting in digressions and anecdotes at every stage. The writing is effortless, or at least appears so. The book took me ages to read, not because it is turgid or difficult (quite the reverse), but because there were so many things I wanted to learn more about that I found myself taking a 10-minute detour here, an hour diversion there, sometimes several times on a page.2

Part II (Travelling the Blue Machine) is about the things that move across and through the oceans---light and sound (with their roles reversed compared with those in air), nutrients, organisms, people, vessels and goods. Even more than in Part I, Czerski her shows herself to be a modern renaissance woman, anchored in physics, but effortlessly ranging across all the sciences, ecology, history, geography, anthropology and more to take a holistic, naturalistic approach to her subject. This part is the ocean as a set of habitats, as a set of interlocking ecosystems, as a world with different rules, rhythms, and characters from those of the land. It is also (as is the whole book) about the ocean as a huge, powerful, energetic, vital and yet changing presence; the majority presence on the face of the Earth.

Part III (The Blue Machine and Us) is the short part, comprising a single chapter called Future. This chapter is about sustainability---about the large changes (really the damage) that humans are bringing about, remarkably quickly, to the oceans and the life in them. Here, Czerski moves from describing the mechanisms of the Blue Machine, and the nature of its ecosystems and inhabitants, to humanity's impacts on the oceans, whether from burning fossil fuels, from using the ocean as dumping ground for wastes, or from allowing plastics to find their way into the marine environment. She outlines the resulting changes to ecosystems, the loss of species, the changes to ocean currents, levels of sea ice, and the acidity of the ocean. She also documents the excess energy being absorbed by the ocean, and its consequent rising temperature. The chapter is prefaced by a quote from a NASA astronaut:

You can't protect what you don't understand.

And you won't, if you don't care. --- Lacy Veach

If everyone in the world read this book, there would be surely be much more understanding, and perhaps more caring.

Nearly thirty years ago, I co-write a book on sustainability with my friend, the ecologist Tony Clayton. He led the writing on most of the chapters, since he actually knows something about the environment, while I led on things like non-linearity, critical points ('tipping points'; the straw that breaks the camel's back), feedback loops, and complex adaptive systems. That book is extremely dated and there is no reason to read it today but what frightens me most now is the same thing that worried me most then then---the possibility that incremental changes we make can lead to large, unpredictable changes in the Earth's response, perhaps amplified by positive feedback loops. For example, as we melt the permafrost, releasing the methane trapped in it, this causes a spiral of further warming. We might cross thresholds from which it is hard or, in practice, impossible to return, twisting a planetary ratchet.

More than anything else, then and now, I think it's hard for people to understand just how large an impact humanity has on the planet, its systems and its occupants. The Earth seems so large, and people seem so small, while greenhouse gases are invisible and plants and animals are so numerous that it's hard for to get our heads around the fact that eight billion of us---eight thousand million; 8,000,000,000---collectively, with our machines and tools and constructions, have highly material impacts on almost all aspects of Earth's biosphere, atmosphere, land, and oceans. It's not so much that the Earth itself is fragile---the Earth will be fine almost whatever humanity does---as that the life support systems for humans and countless other species have limits that we are constantly pushing against and testing, perhaps to destruction.

There are other animals---whales and, as Czerki discusses, Bluefin Tuna---for whom the Earth perhaps doesn't seem so small. They travel more than the circumference of the Earth every year under their own power. I wonder whether, if humans could do this, it would bring a different perspective, just as astronauts frequently describe a transformative new appreciation for the pale blue dot that is our home once they see it from space.

There's a statistic in the book that amazed me, and that perhaps helps demonstrate concretely just how large our collective impact is. Czerki says that we produce 1.4 cubic metres of concrete for every person on the planet each year. A metre doesn't seem that big, but volumes are deceptive. The volume of a typical human is only about 0.07 cubic metres (66.4L = 0.066m³, according to Wolfram Alpha3), so that's 20 times the volume of humans in new concrete each year (and nearly fifty times our mass, since concrete's density is about 2.4 kg/m³). That's over 3 tonnes of concrete per person ever year. These are truly planetary scale quantities.

You should read Blue Machine. It is one of the best, and most important, and most urgent, I have ever read. And while it is a sorrow of sorts, it is also a joy.

-

and I have a Ph.D. in physics ↩︎

-

The book has footnotes, too. My friend, Greg Wilson, in his co-authored article with Jess Haberman, Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Technical Book says 'and remember that nobody reads footnotes.' Itʼs a good article, but as my first thought on reading it was 'I almost always read footnotes'. I bet Czerski does too. Certainly the book is full of them, and the are definitely worth your time, often providing further delightful digressions to the delightful digressions in the main text. But I suppose, if youʼre the sort of person who reads footnotes, youʼll read this and would read hers anyway; and if you are the sort of person who doesnʼt, you wonʼt read this. So this is pointless footnote. Fortunately, however, no one reads footnotes so it won't trouble anyone. ↩︎